This article is part of our Collette Calls series.

This was initially designed as a presentation as part of PitcherList's PitchCon event at the end of May. I was not able to do the presentation due to a death in the immediate family early Saturday, so I present it to you in this format.

I began tracking new pitches in the spring of 2014. I was in between full-time jobs, and doing a lot of podcasting with Paul Sporer around freelancing writing gigs. Paul and I were doing some work with Jensen Lewis around that time as he began his post-career media work, and we got onto the topic of talking about new pitches. I used that conversation to connect with Josh Zeid online and get his opinion on them as well, which formed the basis for me tracking new pitches that spring. The piece was so popular that I started the effort the following spring, and have continued it every spring since. What I had never sat down to do was to compile the overall lists into a singular report to see what the data was showing us and to see if there were any trends. Given that we have not yet seen a new pitch thrown in a 2020 regular-season game, those newsbits from this spring are not part of this discussion.

I went back and looked at the new pitch lists from 2014-2019 and compiled the data into a Google Sheet which contains a comprehensive tab as well as tabs for individual years for your review. What did I learn after reviewing the previous six seasons of work?

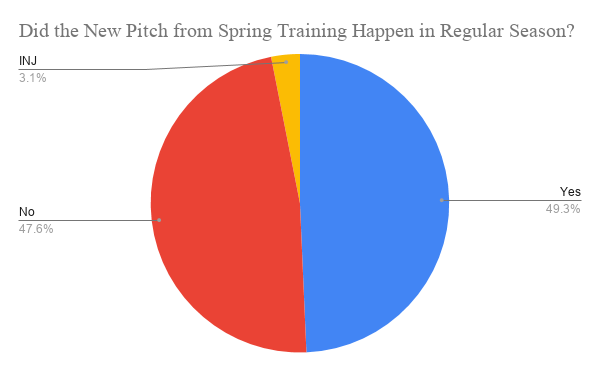

My gut feeling has always been roughly half of the guys who talk about using new pitches, or changing the frequency of using a pitch, actually do so in the regular season. Turns out my gut was right, after reviewing 290 newsbits from 215 pitchers from 2014-2019:

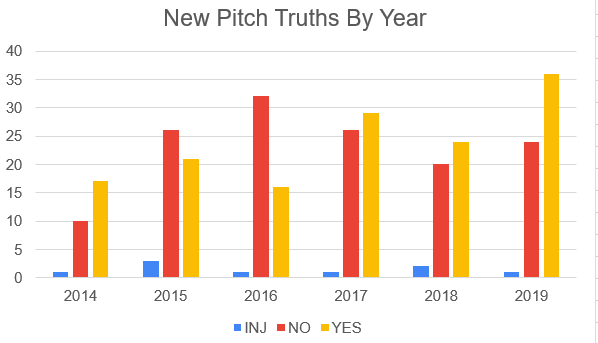

I want to break down this high-level view season-by-season, first in chart form, and then looking at individual success stories each year and why I have stuck with this project as long as I have. First, a breakdown of the stories by year:

The initial year was a great year. Most pitchers who said they were changing things that regular season followed through with their actions. In 2014:

- Jake Odorizzi scrapped his straight-change for a split-change, and saw his strikeout rate jump from 18 percent to 24 percent.

- Phil Hughes threw away his slider, added a cutter, and his strikeout rate jumped from 18 percent to 21 percent while lowering his opponents' batting average 31 points.

- Kevin Jepsen added a changeup, improved his strikeout rate from 22 percent to 29 percent while lowering his opponents' batting average 84 points.

2015 was the opposite and more pitchers left the new pitch utilization in spring training, but there were still a few standouts:

- Trevor Bauer added a two-seamer, increased his groundball rate while lowering his opponents' batting average by 25 points.

- Max Scherzer added a cutter, improved his K-BB% from 21 percent to 27 percent while lowering his opponents' batting average by 30 points.

- Carlos Martinez doubled his changeup usage, lowered his ERA by a full run while lowering his opponents' batting average by 14 points.

2016, summed up in a GIF:

Pitchers had a lot to say that spring, but few followed through on those words in the regular season. In fact, I could only find two good examples of the work paying off that spring:

- Drew Pomeranz added a cutter while moving from the bullpen to the rotation. He improved his strikeout rate nearly four full percentage points and lowered his ERA by half a run.

- Jon Gray added a new curveball (in Coors!) and lowered his ERA by nearly a full run, improved his strikeout rate six full percentage points, while lowering his opponents' batting average 69 points.

A smart man may have ended the pursuit of new pitch knowledge at this point because 54 percent of pitchers to that point had in fact not followed up their spring words with regular-season actions, and 2016 saw two lies for every truth. That is a fun drinking game, but a frustrating one when pursuing a passion project. That said, I stuck with the new pitch tracking, and have been rewarded with more truths than lies in each of the past three seasons.

2017 had a few notable success stories:

- Josh Hader came to Milwaukee camp as a rookie, worked on his changeup, and threw it seven percent of the time out of the bullpen. Ironically, he has rarely thrown the pitch since that breakout rookie season.

- Jimmy Nelson added a split-change to his repertoire that spring, posted a career-best ERA and improved his strikeout rate 10 full percentage points.

- Kirby Yates added a splitter, saw his strikeout rate jump from 27 percent to 38 percent while lowering his opponents' batting average 45 points, which became the launching point of this three-year amazing run from the San Diego reliever.

2018 saw fewer new pitches being discussed, but that did not limit the success stories:

- Lance McCullers worked hard on his changeup, and saw his ERA drop by half a run and his opponents' batting average dropped 34 points with a modest two-percentage-point gain in his strikeout rate.

- Marco Gonzales brought back the cutter he had prior to his TJ surgery in St. Louis and mostly picked up where he left off, posting a career-best strikeout rate, WHIP and ERA.

- Trevor Bauer worked hard on the slider, and improved his strikeout rate by four percentage points, lowered his opponents' batting average 59 points, and was in strong contention for the Cy Young until a late-season injury.

2019 saw the most new pitches documented in the history of this project, and we saw some notable breakouts:

- Frankie Montas (more on him later) added a splitter and improved his profile from a low-end ROOGY type to a front-line starter profile.

- Chris Paddack came to camp as a rookie, said he was developing a new curveball, and threw the pitch 10 percent of the time last season during his breakout rookie campaign.

- Martin Perez added a cutter and improved his strikeout rate five full percentage points and lowered his opponents' batting average 49 points from the previous season.

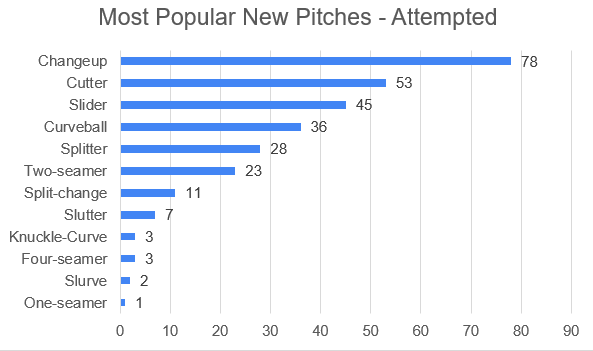

The types of new pitches attempted by pitchers vary, but there is one particular pitch more popular than the others:

The average fastball velocity continues to climb on an annual basis, so it would make sense pitchers want to take advantage of batters sitting on the fastball to disrupt their timing with a changeup. The problem with the changeup is that it is a pitch thrown to look like a strike rather than one thrown in the strike zone. If a pitcher struggles with their fastball command and falls behind in the count too frequently, it is unlikely they're going to throw a changeup down in the count to catch up. In 2019, just 12 percent of pitches thrown while the pitcher was down in the count were changeups.

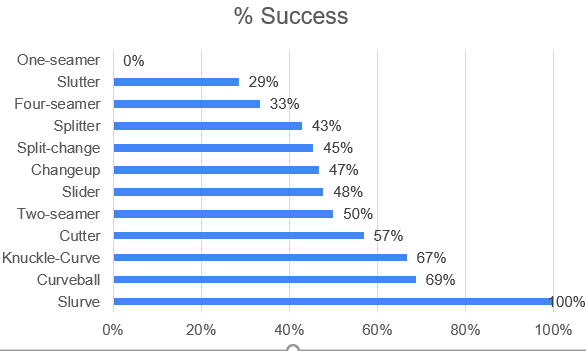

Therefore, it should not come as much of a surprise to see that new changeups in season are a hit and miss adventure. However, breaking balls - curves, slurves, and cutters, have more stickiness.

The thing about new pitches it that just their mere presence does not guarantee any future success. It can certainly help, but I can find as many examples of indifferent outcomes the past few seasons as I can success stories. It is not about the new pitch as much as how the pitcher utilizes the new pitch, which is why I want to focus on what Frankie Montas did in 2018.

Pitchers do not add new pitches out of boredom. They add new pitches with a purpose, which is driven by multiple factors. Pitchers lose velocity as they age, so we see them adding cutters, or throwing fewer four-seam fastballs as they look for different ways to succeed. 2012 David Price would not recognize the way 2019 David Price pitched. The younger Price blew away hitters while the elder Price strategically attacks them with more emphasis on command than velocity. Some pitchers have two good pitches, but lack an effective tertiary offering and see their numbers explode the third time through the order. Other pitchers want to chase the money starting pitchers or high-leverage relievers earn on the open market and want to be more than a situational reliever whose success is limited by severe platoon splits. This is where Montas found himself heading into the 2019 season. As I covered in my last installment of Collette Calls, it was not the new pitch itself as much as how Montas used it that led to the success the young hurler found last year.

If you only look at pitchers such as Yates or Montas adding a splitter, you may find it to be the magic pitch and just plan on chasing those types of pitchers each spring. 17 of 39 pitchers who reported to be working on a splitter or a split-change during the offseason used it in the regular season. For every Yates or Montas, there has been Heath Bell (2014), or Tyler Mahle (2019). What made Montas so special was how he utilized the pitch and what it did to the approach hitters took against him.

Prior to 2019, when Montas was behind in the count, he threw a fastball 78 percent of the time, a slider 21 percent of the time, and a changeup just seven times out of 531 pitches. So, you can hardly blame Hanser Alberto for looking this bad in a 1-0 count when Montas forked up a splitter behind in the count (all GIFs courtesy of @AugustineMLB)

Sure, Alberto has rarely seen a pitch he did not like, but he was clearly sitting on hard stuff there and ended up swinging half a foot over that pitch. This is an example of optimal use of a new pitch because where Montas previously had a "show-me" changeup he threw when he was up in the count, hitters now cannot look for the fastball and adjust to the slider and have to protect against the pseudo-strike splitter.

The reason Montas came up with the splitter in the first place was because he was even more predictable against lefties, but with the new weapon and a willingness to throw it at any time in the count, lefties could no longer zone in on fastballs and sliders and tee off. He could now run them in with heat, or fade them away with the splitter forcing the hitter to cover both sides of the plate:

Now, lefties had to cover both sides of the plate as well as up and down in nearly any part of a count leading to defensive-looking swings such as the one by Dwight Smith which led to him swinging over a back-foot slider:

Now, let's look at some pitchers who said they're working on a new pitch for 2020 that could take a similar step forward that Frankie Montas took in 2019.

Joey Lucchesi is working on a changeup, and he needs it to go to the next level for a few reasons. His repertoire last season was a sinker, a cutter, and the churveball - a changeup/curve hybrid. It is such a hybrid pitch that Baseball Savant classifies it as a changeup, but it doesn't act much like one because it moves glove side. Lucchesi has two main faults - an inability to be effective deep into a game and his righty-lefty splits.

He pays a huge Times Through The Order (TTO) tax:

| SPLIT | ERA | WHIP | K-BB% | AVG | HR/FB | wOBA | HARD% |

| 1ST | 3.70 | 1.13 | 20% | 0.222 | 13% | 0.284 | 35% |

| 2ND | 3.12 | 1.09 | 17% | 0.221 | 11% | 0.268 | 35% |

| 3RD | 7.26 | 1.74 | 3% | 0.283 | 18% | 0.385 | 44% |

Lucchesi's ERA drops from 4.18 to 3.41 if we pretend he never went a third time through the order. His 1.22 WHIP would also drop to 1.11. The same issue which causes this bleeds over into his righty/lefty splits.

| SPLIT | TBF | AVG | OBP | SLG | K-BB | GB/FB | HARD% |

| vs RH | 528 | 0.236 | 0.295 | 0.422 | 15% | 1.1 | 41% |

| vs LH | 158 | 0.221 | 0.301 | 0.350 | 13% | 2.3 | 25% |

His batting average is not much different, but notice the spike in slugging percentage, hard contact and the types of batted balls generated. Lefties struggle to elevate him, yet righties do not have the same struggles, and hit 19 of the 23 homers he allowed last season. The HR/FB rate was not out of line, but it is unusual to see such a dramatic GB/FB split based like this.

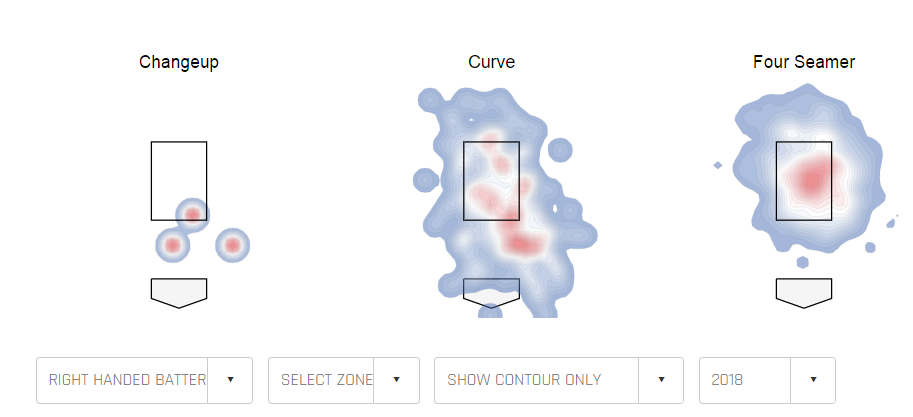

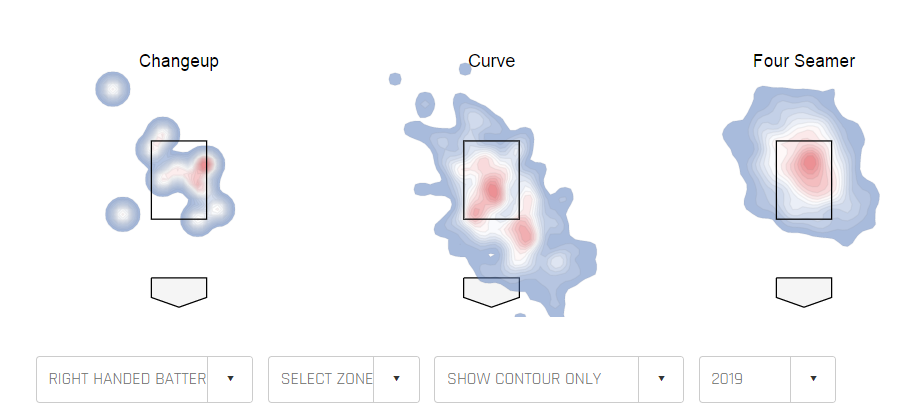

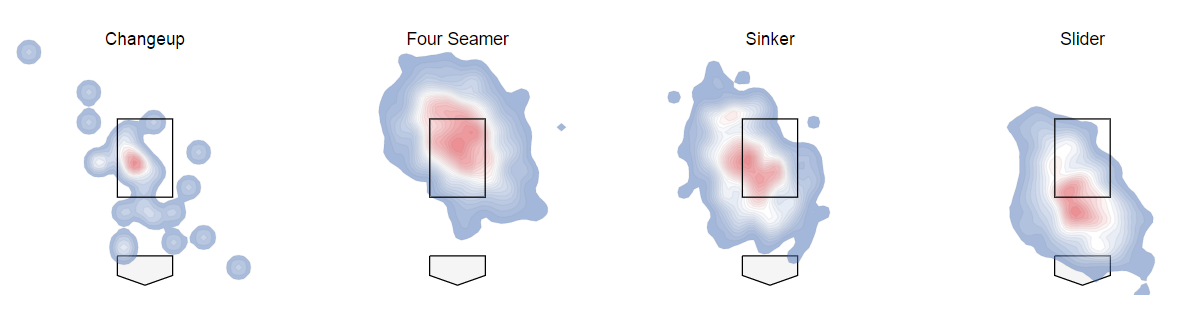

Lucchesi, to his credit, does throw three pitches to righties:

However, notice the primary location of these pitches. The churve is living in the zone quite a bit, and when it is out of the zone, it's still down over the middle of the plate. A lefty changeup to a righty fades away from righties, but the churve isn't doing that. The cutter is mostly being thrown in on the hands while the sinker is being thrown away. The first two times through an order, the batter is not sure which mixture will come around, but there are only so many combinations Lucchesi can use with that repertoire, so the batter has a better clue where to zone in the third time around.

A changeup which fades away from the righties and gives him another velocity variety to showcase should do him wonders. His sinker and cutter have nearly identical average velocities, while the churve comes in 12 MPH slower. A changeup would split the difference between those pairings and give him a chase pitch which fades away from the lefties creating another zone the hitter has to respect. Fixing the righty/lefty issue should also reduce (it is never eliminated) the TTO tax he paid last season.

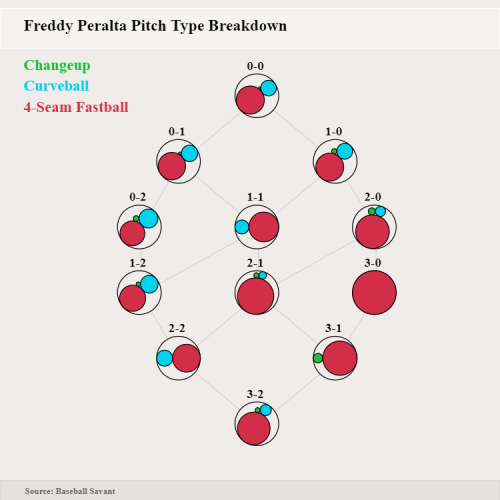

Freddy Peralta is working on resurrecting his slider. Last season, he stumbled out of the gate amassing a 8.31 ERA over his first five starts and essentially losing his spot in the rotation. Allowing seven home runs in 21.2 innings will do that to a starter. He settled down as a swingman the rest of the way, but still had a 4.81 ERA the rest of the season after the terrible start. Still, it is tough to throw away a pitcher who struck out 115 batters in 85 innings as Peralta did last year with his fastball and curve.

Peralta's fastball is well known for its high spin rate, and how the perceived velocity of the pitch due to the extension in his delivery gives the pitch deceptive hop. The curveball is the alternative-look pitch because he has never been able to develop anything more than an effective changeup. The fastball/curveball look could work in the bullpen, and with better command, but it would be an unusual pairing in today's bullpen where fastballs and sliders reign supreme.

Peralta not only has a limited repertoire, but also was surprisingly bad against righties last season.

| SPLIT | TBF | AVG | OBP | SLG | K-BB | GB/FB | HARD% |

| 2019 vs RH | 230 | 0.280 | 0.338 | 0.526 | 22% | 0.8 | 42% |

| 2019 vs LH | 152 | 0.219 | 0.239 | 0.344 | 17% | 0.6 | 33% |

| Career vs RH | 394 | 0.211 | 0.279 | 0.389 | 22% | 0.7 | 40% |

| Career vs LH | 309 | 0.236 | 0.357 | 0.417 | 15% | 0.6 | 40% |

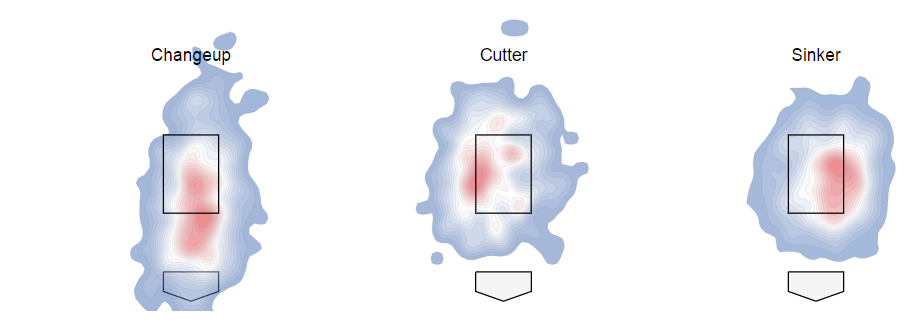

This was not the case in 2018, and while we are still talking about a somewhat small sample, there was a stark difference in his effectiveness last year against righties. Ironically, he did better against lefties last season than he did righties. I went to the contour maps at Baseball Savant and see two things - more elevated fastballs last year and too many curveballs within the strike zone.

In fact, Peralta added velocity to his fastball last year over 2018, but you'd never know it by his outcomes:

| SPLIT | PITCHES | Avg MPH | BA | xBA | SLG | xSLG | wOBA | xwOBA |

| 2018 4FB vs RH | 530 | 91.0 | 0.120 | 0.133 | 0.214 | 0.246 | 0.202 | 0.228 |

| 2019 4FB vs RH | 720 | 93.8 | 0.283 | 0.249 | 0.512 | 0.474 | 0.358 | 0.324 |

| 2018 CB vs RH | 150 | 76.5 | 0.077 | 0.196 | 0.077 | 0.310 | 0.112 | 0.248 |

| 2019 CB vs RH | 211 | 77.2 | 0.256 | 0.224 | 0.513 | 0.386 | 0.337 | 0.273 |

The 2018 numbers were never sustainable, but the expected numbers show that 2019 should not have been as bad as it was for him. Peralta's apparent fault was that he struggled with his command on the fastball, so he fell behind in the count, and became very predictable when that happened:

In his current form, Baseball Savant says based on velocity and movement, Peralta is similar to Chris Paddack. Based on batted-ball profile, Peralta was similar to the likes of Trevor Bauer, James Paxton, Sean Manaea and Robbie Ray last year. The latter group each throw the slider that Peralta is now trying to add.

Here's the new slider Freddy Peralta was throwing in the Dominican winter league.

He was already due for some improvement (3.80 SIERA) but if he adds a legit strikeout pitch, which he currently lacks, he could be an interesting guy if he gets some starts at some point pic.twitter.com/L2tlHp7djm

— Ben Palmer (@benjpalmer) February 15, 2020

If you want to see what that slider looks like, see below. Peralta's results in the winter league this offseason were amazing:

- Innings: 20

- Baserunners: 9

- Strikeouts: 34

- ERA: 1.35

That slider will give him some velocity in between the fastball and the curve and give batters something else to think about when they're in a fastball count. Given that Peralta has not been able to develop an effective changeup, he can use his curveball as his offspeed pitch and use the sharper break and increased velocity of the slider in any stage of the count if he truly feels as comfortable with the pitch as the winter league newsbit suggests. Peralta, with this slider, could become what Garrett Richards has done in the more recent stages of his career where he scrapped the changeup and went with the fastball and two breaking balls as his main pitches. Hopefully, Peralta can avoid the arm injuries which have disrupted Richards's career the past few seasons.

Brad Keller is adding a curveball. He appears ready to unleash the pitch this year as his de facto change-of-speed pitch while he continue to work on his changeup. Keller's repertoire to date has been primarily two different fastballs, a slider and a rarely-used changeup. That profile lends itself to platoon splits, and Keller's are rather obvious:

| SPLIT | TBF | AVG | OBP | SLG | K-BB | GB/FB | HARD% |

| 2019 vs RH | 345 | 0.243 | 0.307 | 0.393 | 8% | 1.8 | 38% |

| 2019 vs LH | 364 | 0.251 | 0.350 | 0.370 | 7% | 1.6 | 36% |

| Career vs RH | 656 | 0.241 | 0.293 | 0.353 | 9% | 1.9 | 35% |

| Career vs LH | 636 | 0.258 | 0.356 | 0.368 | 6% | 1.9 | 33% |

It does not show up in the batting average, but note the difference in OBP as Keller's approach against lefties with his current repertoire appears to be pitching around them to get to another righty. Last season, this approach led to a 12 percent walk rate against lefties versus a seven percent walk rate against righties:

The changeup is almost a nothing pitch as he threw it to righties two percent of the time, and is, by Keller's own words, a continual work in progress. The fastballs and slider range from 87 to 93mph, so Keller currently lacks a true timing disruption pitch that has significant velocity separation. Keller is fully aware of the need of adding this pitch:

Keller's current strikeout rate and whiff rate are both in the bottom 20th percentile for qualified MLB pitchers. The addition of a curveball is not as much about covering another part of the zone as much as it is disruption of timing. It would allow him to present a more well-rounded repertoire in terms of pitch shape and velocity to both lefties and righties and change his profile from a back-end starter to someone who can pitch in the middle of a rotation.

There were many new pitches being developed before the baseball season was postponed, but these are the three I am most excited about as they have the potential to elevate endgame plays to a more substantial role if we have baseball in 2020.